Reposted from MobLab and written by Ted Fickes

In Brazil, there is City of Dreams. It’s a networked campaign for places where diverse groups and people organise and advocate for climate-friendly energy, parks, transportation and waste systems. Local leaders address these issues in elections and policy – guiding national and global governments to take seriously people’s demands for action on climate change.

Can you use local politics as a path to engaging millions of people in conversations about climate change policy? That’s the question City of Dreams seeks to answer. Along the way, campaigners are picking up lessons on convening, open campaigning, nimble campaigning and sharing metrics.

Most people feel powerless in the face of climate change. They know it’s important and can see impacts. But solutions often need global or national action. Governments seem increasingly dysfunctional and far removed from people’s daily lives.

Building on the “Bus of Dreams” project that brought people together to shape São Paulo’s transportation system in 2015, City of Dreams convened and engaged a diverse coalition able to reach people with a wide range of interests. The goal: make climate change a central conversation in upcoming mayoral elections across Brazil.

The path to transforming national climate conversation has evolved into an example of how networked convening doesn’t simply create coalitions but instead provides the lubrication needed to keep a complex machine – dozens of groups with different goals, missions and messaging styles – together. City of Dreams informed with data and resources and prioritised understanding each group’s needs and strengths.

Looking back, some of the campaign’s greatest successes – and lessons – resulted from the ability to gather data that guided pivots away from established plans. For example, a big investment in a web-based organising platform quickly proved ineffective. The results forced a decision many campaigns face: when do you trust the data and pull the plug on a big idea (and when or why should online platforms be used)?

The campaign team also released metrics: how many people were signing up to events / sharing messages, etc. Campaigns often look at this kind of data as internal only. It could tip the campaign’s plan to opponents or look lackluster in the public’s (and supporters’) eyes.

The result fit with the theme of open campaigns. People across the convening – and even media and the public – better understood the campaign messaging and performance. They understood what the campaign was trying to do and how getting people involved would make it work.

Convening a diverse network: Real challenges. Big opportunities.

Convening and guiding a network may quickly scale up potential impact. But don’t underestimate the time it takes or resources needed to support a network. Local, on the ground relationships are valuable and hard to build from far away.

City of Dreams required engagement and support from a broad range of community organisations in multiple cities hundreds or thousands of kilometers apart. The small core depended on other groups and volunteers.

Convening offered resources like on-the-ground expertise, support and volunteers. New partners brought together allies from a range of issue and business interests ranging from parks and clean energy to transportation and air quality. Collaborators could share resources and expertise ranging from communications to data to networks.

The team didn’t create and staff a coalition. Instead they convened organisations with shared interests and helped each one play to its own strengths using shared resources provided by the team – information, media support, a public engagement platform, metrics, and organising support for on the ground events.

Gabriela Vuolo, campaigns director at Purpose Brazil, told us that any good network convening work requires brutal honesty about the strengths of the groups involved and their boundaries related to the campaign. It’s critical to know what issues each group will talk about and their positions on those.

This takes time. It was more time, Vuolo learned in her role as convenor, than she often had to offer.

“If done properly and carefully you have to have someone really dedicated to the job, knowing all the partners,” says Vuolo.

As City of Dreams sought to work in three cities – Recife and Rio de Janeiro in addition to São Paulo – it struggled with nuanced local relationships. “The things that didn’t work,” Vuolo says, “it’s not that they didn’t work but they could have been much better if we had someone dedicated to the city.”

It’s tough to parachute into a campaign by conference call. When you’re convening diverse groups – helping them play to their strengths and jumping in where it works best for them – you aren’t telling them what to do. You’re building trust and investing the strength of existing relationships. The biggest difficulty, Vuolo shared, is understanding the relationships – the history – of groups and people in/around them.

City of Dreams wasn’t just about convening diverse organisations – it was also about bringing together thousands, even millions, of Brazilians. The campaign team learned that engaging people online is a lot like convening: you need to be where the people are.

When the strategy is right be willing to change tactics (and organise people where they are)

It took the campaign just two weeks to realise its investment in an online engagement/voting platform wasn’t going to work and they had to move forward without it. Trusting data and being flexible paid off in the long run.

You got to know when to hold ’em, know when to fold ’em, know when to walk away and know when to run.

– The Gambler, 1976

Residents of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Recife interacted with City of Dreams by sharing their vision for how their city should deal with energy, green space, mobility and waste systems. In other words: parks, clean energy, recycling and trash, transit. City residents deal with these issues every day in their home, on their commute, running errands, exercising and more. Thus, City of Dreams was able to make climate change issues feel real to everyday Brazilians.

City of Dreams also encouraged people to review ideas shared by other people and, of course, to react to each city’s own plans. The more people talk about their ideas, the more likely they are to engage in supporting them when mayors and cities debate policy (and the more effective their support will be).

People would be sharing, reviewing and voting on their City of Dreams ideas and vision online – not in public meetings or by paper ballot. This process would also happen more or less simultaneously in three cities.

The campaign team, logically enough, decided to build a website. It would be an online platform for voting, sharing and spreading the word. The platform would grow to be an online community connecting people and ideas. It could evolve into an organising tool when it came time to hold politicians and decision makers accountable to people’s ideas.

The platform launched as an independent website. Two weeks in it was clear nobody used the site.

City of Dreams already had a Facebook page and the team used the page to tell people about the new platform. People were visiting the site but not exploring it. They weren’t going past the home page to read about and vote on ideas.

“After two weeks we gave up the website and put all our content on Facebook,” says Ana Neca, Project Manager at the Purpose Climate Lab.

On one hand, the decision made sense: Facebook is widely used in Brazil and it’s where people talk to each other and share ideas. On the other hand, it meant abandoning a key tactic and a big investment. It also meant giving up on the ability to control and use the data gathered on users. If you build your own platform you can ask people about email address, name, location, social profiles, interests and more.

The move to Facebook had offsetting, even unintended, benefits. People started tagging candidates when talking about and voting on City of Dreams ideas. That raised candidate awareness and engagement. People also tagged friends and family outside the three focus cities. This helped create a national conversation and raised awareness among national media.

Opening up the campaign: Sharing metrics and leadership

The campaign team opened up its metrics to convening partners and allies. This built trust and provided everyone with clear insights into every group’s role and how their efforts impacted the campaign. Transparency also provided new partners with clearer ideas of what was working, what was needed, and how to efficiently and effectively add value.

Campaign leads Gabriela Vuolo and Ana Neca both spoke to us about the importance of convening a broad range of groups and city residents during elections to bring broad pressure onto mayoral candidates. As City of Dreams progressed, the campaign team (a group of four) understood they didn’t have enough people to lead offline events in all three cities. Collaborating groups were short on resources, too, and often only focused on a specific city or issue.

Along the way, the team decided to open up campaign implementation and progress to partners, the media and public. For instance, the campaign used a third-party service in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo to monitor candidate mentions of City of Dreams messages. They tracked mentions in Recife on their own. The point was to track results, test, adjust and optimise messaging provided to partners.

Eventually, the team chose to share message monitoring data with partners – primarily through an internal email list. Neca and Vuolo credit sharing metrics with helping partners understand what was working, what wasn’t, and what to test.

“We didn’t share only monitoring data, but all campaign materials were conceived and shared with the coalition,” Neca shared an email about their approach. This reflects the open, network-support role that the Purpose campaign team took in City of Dreams. The goal was to provide strategy, support and materials, not tell people what they had to do or to have a public-facing leadership role.

“Transparency got stronger as we saw its results. Telling partners about the methodology we used to analyze results and building statements in a collaborative way inspired other organisations to do the same,” Neca told us.

Previous MobLab stories have reflected on the power of open campaigning – letting partners and even the public see plans, metrics and methodologies so they can help lead. City of Dreams is something of a hybrid open campaign. There is a high premium on transparency between the campaign team at the hub of the network and partners. But a culture of documenting results and making processes available has helped grow the network and scale impact. Neca and Vuolo identified two ways in which the campaign has benefited:

- Improved results from organisations that are already involved in campaigning (more inspiration, learning from experience, sharing new ideas);

- Inspiring other partners to engage and serving as a start point for those who want to begin but don’t know how.

An open and collaborative approach is also helping engage and train volunteers for offline events. City of Dreams partnered with Engajamundo, an organisation that connects youth with environmental action, to recruit volunteers who lead local events.

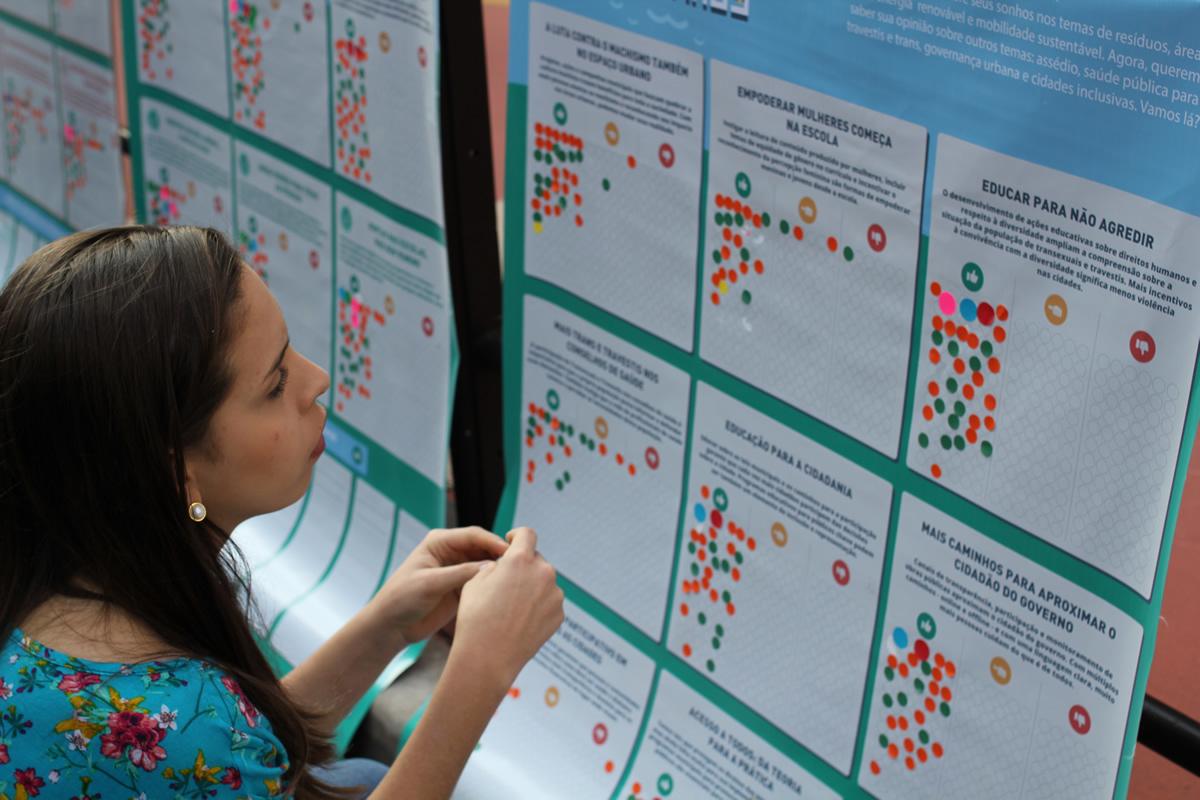

Often, this looks like street teams: people in busy city locations who talk to passersby about City of Dreams and solicit their vision for transportation, green spaces or energy in the city.

City of Dreams voting across Brazil

Engajamundo organises youth across Brazil to volunteer and take action on environmental issues. Engajamundo members and volunteers helped organise and lead offline City of Dreams voting events in 2016.

Doing this work is a big ask of volunteers but, with support from partners, the campaign team could focus on creating training materials, scripts, and outreach tools for use by local convening partners and people on the ground. Leading up to the October, 2016, municipal elections, the campaign held 63 offline events that engaged nearly 7,500 people in 16 cities. The number of cities involved is an indicator of how people took the campaign, which intended to focus on only three cities, and made it their own.

Around the world, climate change is impacting the health of parks and coastlines, food availability, water and sanitation, and the value of clean energy. Capital letter Climate Policy is debated at the national and international level but people feel climate change at the local level. Municipal, state or provincial governing bodies can weigh in, often much more quickly.

Organising around climate policy at the local level, even without talking about climate, is something people can dig into, talk about, and take leadership over. The City of Dreams campaign is testing this approach, with success, in Brazil. They’re also learning how diverse organisations can engage in climate advocacy if given information that works for them, data and metrics, and other network support.

Learn More

- Read the Purpose Climate Lab case study of City of Dreams.

- Stay in touch with Cidade Dos Sonhos (City of Dreams) on the web, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

This article was made possible in part through support of Purpose Labs’ commitment to providing global campaigners with innovative ideas and strategies to help them win bigger.